31 January – 10 May 2026

Over 50 artists across 100 years explore British portraiture with The Ingram Collection and Dorset Museum & Art Gallery

In 2026, Dorset Museum & Art Gallery will stage an extensive exhibition combining one of the UK’s leading collections of modern British art – The Ingram Collection – with its own, resulting in an exploration of the concept of image and portraiture.

People Watching will feature around 50 works of sculpture, paintings, drawings and photography, including works that have never been displayed publicly before, spanning a century and more, from 1915 up to today. The exhibition seeks to discover what portraits can tell us about the artist and sitter, whether by simply showing what a person looks like, or by capturing an idea or emotion or through representation.

With work from over 40 individual artists, including some of the most acclaimed names in modern British art such as Elisabeth Frink, Bridget Riley, Stanley Spencer and Henry Moore, as well as lesser-known artists ready to be re-discovered, the exhibition promises to be an extensive and thorough investigation of British portraiture that will leave visitors more informed about the past and more excited about the future. A major part of self-portraits is how the artist portrays themselves, and in doing so revealing their own inner world of personal identity, emotion and state of mind. On display will be a number of these illuminating works, from classic works to modern selfies.

Despite being a champion of the avant-garde and experimental, Roger Fry’s (1866-1934) portraits were usually naturalistic. However, on display will be a woodcut – Self Portrait (1921) – printed by fellow Bloomsbury group members Leonard and Virginia Woolf that employs a more expressionist take on his image with heavy lines and exaggerated eyes, producing an image both austere and compelling.

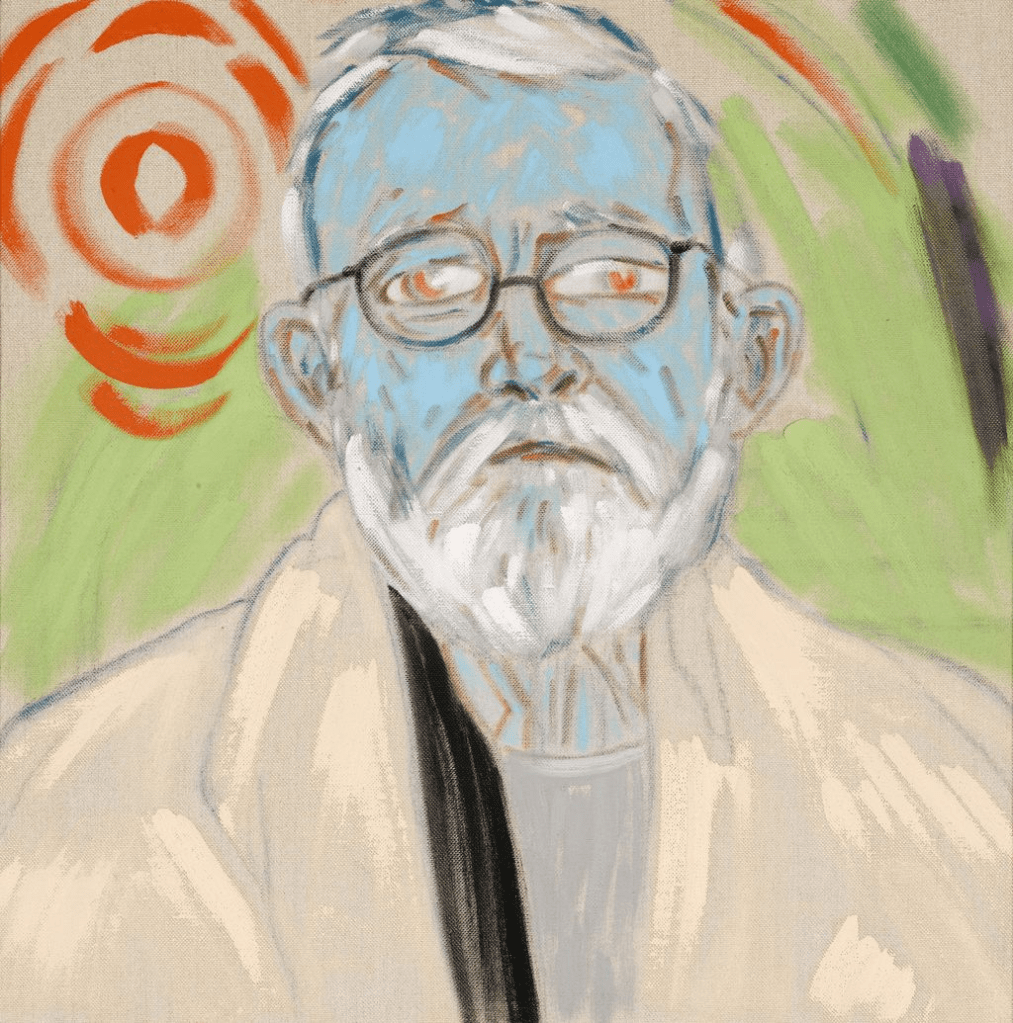

An example of the narratively complex and referential works of RB Kitaj (1932-2007) is included in the show. In Radiant Turquoise Self Portrait (2006) the artist depicts himself with a blue-skinned tint, but the luminous colour also carries an emotional weight. This work, one of the last works he ever produced, is a culmination of Kitaj’s latter period that was punctuated by both critical success and personal grief, as his forlorn expression seems to show.

RB Kitaj (1932-2007) – Radiant Turquoise Self Portrait (2006)

More recent works that show how portraiture has continued to evolve include the painting A Handful of Tears (2013) by Shropshire-based Lucy Jones (b.1955) which captures her tears as she collapses on the floor, highlighting her own fragility and despair. Further works include a series of selfies in paint from Tom Benedek (b.1991), an unusually realistic self-portrait by Terry Frost (1915-2003), a Janus-inspired painting by John Bellany (1942-2013), a highlight of a tattoo by Billy Childish (b.1959) and an expressive etching by Marigold Plunkett (b.1983). There are also portraits of people in professional environments, highlighting the dignity and diversity that can be found in the labour market, and the interesting skills that enable people to live their lives.

Portraits during wartime show contrasting emotions. Justar Misdemeanor (b.1988) depicts the battlefield in the large charcoal work Soldier (1913) where the central figure’s face is hidden with their body in a foetal position showing vulnerability, protection and fear.

The early decades of the 20th century were also when musicians became stars in their own right, shown here with Winifred Nicholson’s (1893-1981) depiction of her friend in Woman Playing a Piano (Vera Moore) in which the music and the sitter become a shared identity. Augustus John (1878-1961) spent three years studying the cellist Madame Suggia for an eventual portrait, of which one of the preparatory studies – perhaps more intimate than the finished product – is featured.

Self Portrait – Elisabeth Frink

In the 1940s Barbara Hepworth (1903-75) was invited to attend the operating theatre at Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Centre in Exeter and as a result produced a group of six paintings and over sixty drawings where the boundaries of art and medicine dissolved. One such is on display here with Fenestration of the Ear (The Microscope) (1948) showing a group of doctors working on a patient with special focus on their eyes in deep concentration. And in a drawing never displayed publicly before will be Elisabeth Frink’s (1930-1993) capturing of the sinister and menacing Moroccan General Mohamed Oufkir from a 1966 photograph, as well as her own self-portrait in sculpture.

Further work includes a scene of seamen ashore by Edward Burra (1905-1976) and footballers in the middle of a match by Hughie Beattie (b.1970). In contrast to work, another section of portraits will look at leisure and play, and how the joy and freedom found in the spontaneity of human life can be captured.

David Remfry (b.1942) has been capturing dancers for decades, from Hull to New York, and in Dancers II (2004) he sketches two couples dancing unguarded. With sweeping lines and splashes of colour, he translates the free rhythm of the scene through the drawing, so the viewer becomes an active participant.

Sport and physical activities offer both depictions of the participant and the act of viewing. In Anita Klein’s Phone call in the World Cup (2010) a man watches the football game on the TV as a woman talks on the phone. Despite facing in opposite directions and sharing a cramped sofa, Klein’s use of colour and harmonious rendering gives the scene warmth rather than alienation.

The locations of where people choose to relax can also be seen in the stylised draughtsmanship of Robert Duckworth Greenham (1906-1976) with On the Beach (1934), as well as Bridget Riley’s (b.1931) early work Woman at Tea Table (not dated) which is more representational, but hints at the dazzling abstraction to come. A drawing by Elisie Barling (1883-1976) from the 1930s depicts a display of affection while at the seaside between two singers, Norman Notley and David Brynley, who lived openly as a gay couple.

Bridget Riley’s (b.1931) – Woman at Tea Table (not dated)

These join other works including a watercolour by Mary Fedden (1915-2012) of her husband, the artist Julian Trevelyan, a domestic life scene by Michael Ayrton (1921-1975), a Picasso-inspired self-portrait by John Craxton (1922-2009) and a musical ink and watercolour by Ceri Richards (1903-1971). Reflecting the deep bonds that exist between family members will be a series of works by celebrated artists depicting their kin.

William Roberts (1895-1980) depicts his own family in Artist and Wife (1940) where the mother juggles both nursing a baby and painting on a canvas while the father looks on and completes the domestic chores. Fellow Vorticist practitioner David Bomberg (1890-1957) suggests the family unit of an outsider variety with his Bargee Family (1919-20) depicting workers travelling down London’s canals in expressive lines.

The negative aspects that can arise from family issues can also be seen on display. Sir Stanley Spencer (1891-1959) draws his then-wife in a restrained, but intense, work – Portrait of Patricia Preece (1929) – made before the pair separated in acrimonious circumstances. In Homesick (2019) Alvin Ong (b.1988) depicts a figure alone screaming in a shifting swirl of movement, while F. E. McWilliam (1909-1992) sculpts the act of fraternal murder in simplified shapes with Cain and Abel (1957).

Family ties will also be seen in the work of other artists including a sculpture signifying maternal intimacy by Rosemary Young (1930-2019), a portrait of his sister by Jacob Kramer (1892-1962) and a scene of intimate domestic bliss by Alan Lowndes (1921-1978). Portraiture also presents the opportunity to capture the essence of a subject in unconventional ways. Exploring the mythic, the imagined and the abstract, and revealing deep truths through imaginative symbology, a selection of works will show the endless possibilities when portraiture meets fantasy.

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) interprets her friend as a spirited rider of conviction against a midnight sky in Iris Tree on a Horse (c.1920s), laden with talismanic symbols of freedom and independence. In Amy Beager’s (b.1988) recent Bobbidi (2021) an other-worldly dancing figure is given angel wings and realised in dazzling colours.

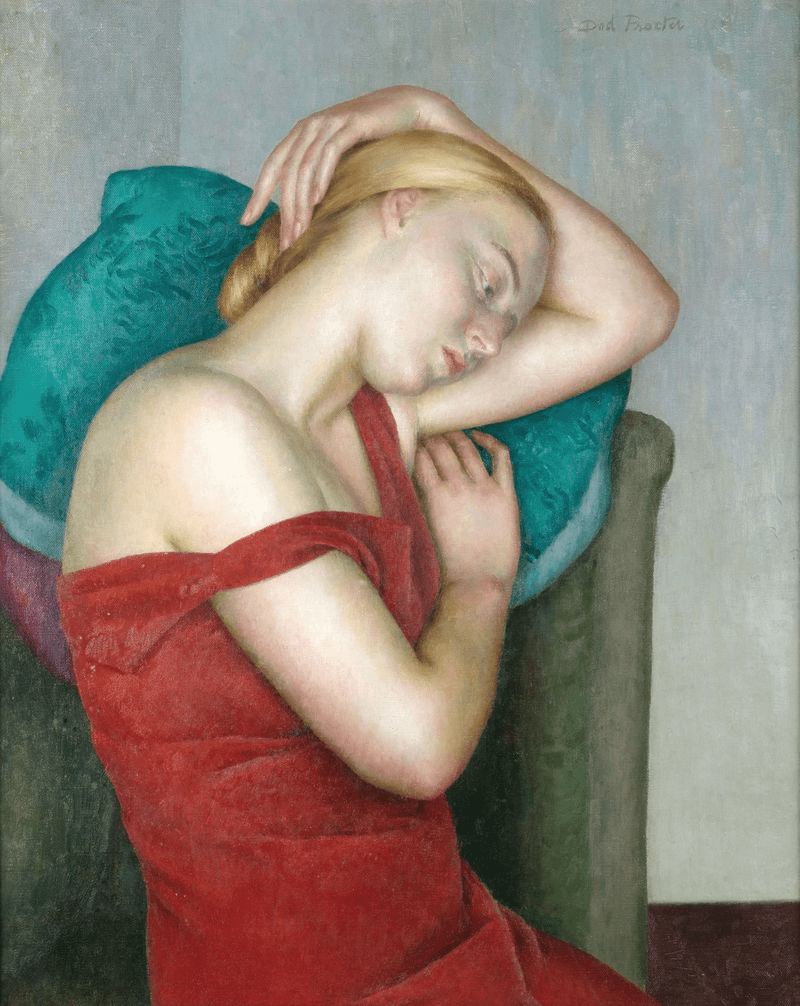

Dod Procter (1892-1972) was celebrated for her portraits of female sitters, and one of her most remarkable will be on display with The Golden Girl (1930). Referencing the heroines of ancient Greece with flowing hair and softly draped clothes, Procter chose to imbue the women of this era with a unique sculptural quality and timelessness.

Dod Procter (1892-1972) – The Golden Girl (1930)

Further journeys into the imagination include work by Aleah Chapin (b.1986) showcasing an unfiltered and natural body, a small-scale face that holds a powerful gaze by Kofi Perry (b.1998), a Goggle Head by Frink, four reclining figures by Henry Moore (1898-1986) and a larger-than-life sculpture of a head by John Davies (b.1946).

Dorset Museum & Art Gallery Director Claire Dixon said: “We are thrilled and grateful to be working with The Ingram Collection to bring these internationally significant works of art to Dorset, showcasing them alongside our own collection, some of which has never been publicly displayed before. Exhibitions are the life blood of our programme, inspiring visitors to return again and again and this would not be possible without the philanthropic support of organisations like The Ingram Collection. Whether you visit, work or live in Dorset, there will be something for you to enjoy as the exhibition is also supported by works displayed throughout our galleries that will captivate for hours.”

Ingram Collection Director Jo Baring said: “This exhibition is a celebration of the power and versatility of portraiture – how it can reveal, conceal, question and transform. ‘People Watching’ offers a unique opportunity to experience modern British art through the lens of the human face, both familiar and fantastical. We’re proud to collaborate with Dorset Museum & Art Gallery to bring together such an ambitious range of works, some of which have never been seen in public before. It’s a chance to rediscover celebrated names and encounter fresh perspectives from new voices shaping the future of portraiture today.”